NEW FRONTIER

Urbanization of the Global Hinterland

There is nothing spectacular about Parauapebas. The breakneck expansion of this mining town, located on the border between the impenetrable jungle of the Carajás National Forest and the deforested landscape beyond, has left barely enough infrastructure and urban services for its estimated 250,000 inhabitants to be recognized as a city—but still, Brazil’s future is in Parauapebas and other areas in the Amazon.

Of the nineteen Brazilian cities that the latest census indicates have doubled in population over the past decade, ten are in the Amazon. The biggest linchpins for rapid urbanization in the region are major energy and industrial projects taking advantage of vast reserves of untapped natural resources. With the proliferation of hydroelectric dams, mechanized soybean plantations, and intensive mining operations, thousands of migrants have been lured from all over the country in search of jobs and economic stability. Soaring population growth, supported largely by forecasts of robust demand in China and other emerging territories, has intensified urbanization in the last decade, turning the rapidly-growing cities of the Amazon into the world’s last great settlement frontier.

The case of Parauapebas reveals the collateral effects of global capitalism and its impact on the planet’s hinterland—but it also serves as an allegory for urban development in the Anthropocene. In Paraupebas, the frontier is explicitly marked by the river of the same name, which divides the lower town—where most of the workers live—from the Carajás National Forest. What seems to be a clear distinction between “wilderness” and urbanized territory is difused by the logistical operations necessary to guarantee the extraction of massive amounts of iron ore and its transport to worldwide destinations. To the surprise of a visitor who passes through the gate to the Natural Protected Forest, the nature reserve is home to a number of manmade environments, surrounded by dense vegetation along the road that leads to the world’s biggest iron-ore mine. While the airport represents the other gate to the mine complex, “Nucleo do Carajás,” a forest settlement for 6,000 residents, was conceived as a tropical enclave for higher employees of VALE Rio Doce, the company that operates the mine. But the forest is also still inhabited by the Karajá and Kayapó, the native people indigenous to the Serra do Carajás region.

The city of Parauapebas is closely linked to these outposts of human activity in the middle of the Amazon Forest, which are in turn connected via air travel and railway to urban agglomerations elsewhere in the world. Here, the global economy has spurred a process where resource extraction and natural protection go hand in hand. In this frontier zone, the line between nature and city is explicit; at the same time, the distinction is growing blurry. The following depiction of urban development in the area of Parauapebas raises the question of whether the frontier town represents the back-end or the forefront of global capitalism.

1 The Frontier Zone

Like any other special economic zone, the frontier zone represents an exclusive territory that “banishes any obstacle to profit […]—a mechanism of political quarantine designed for corporate protection.”¹ When “the Zone” described by Keller Easterling as an “urban organ of extrastatecraft” meets the frontier, the extraterritorial operation deals with the relationship between development and nature. In the region of Serra do Carajás, the idea of the frontier zone is expressed in the particular way in which natural resources are connected through infrastructure and technology to global flows of capital and goods. The history of this special zone started back in 1967, when Brazilian geologists detected vast reserves of iron ore, manganite, and copper when they landed on a barren hilltop to refuel. The geologists recognized that those spots where vegetation is scarce reveal high concentrations of the valuable metals—decades later, one of the world’s largest iron ore mines has taken its place.

If infrastructure and logistics were the key components that enabled the extraction of raw materials here for the massive demand of the global economy, the frontier zone represents more than an outpost for the advance of development into natural territory. Considering the dimension of the operation and the efforts it takes to assemble manpower and technical equipment, the contemporary frontier also reveals a specific mode of contemporary urbanization. While the iron is used for the production of cities far away from its source, urbanization is meant to create not cities, but rather logistical hubs that allow the flow of people and material needed for the exploitation of nature.

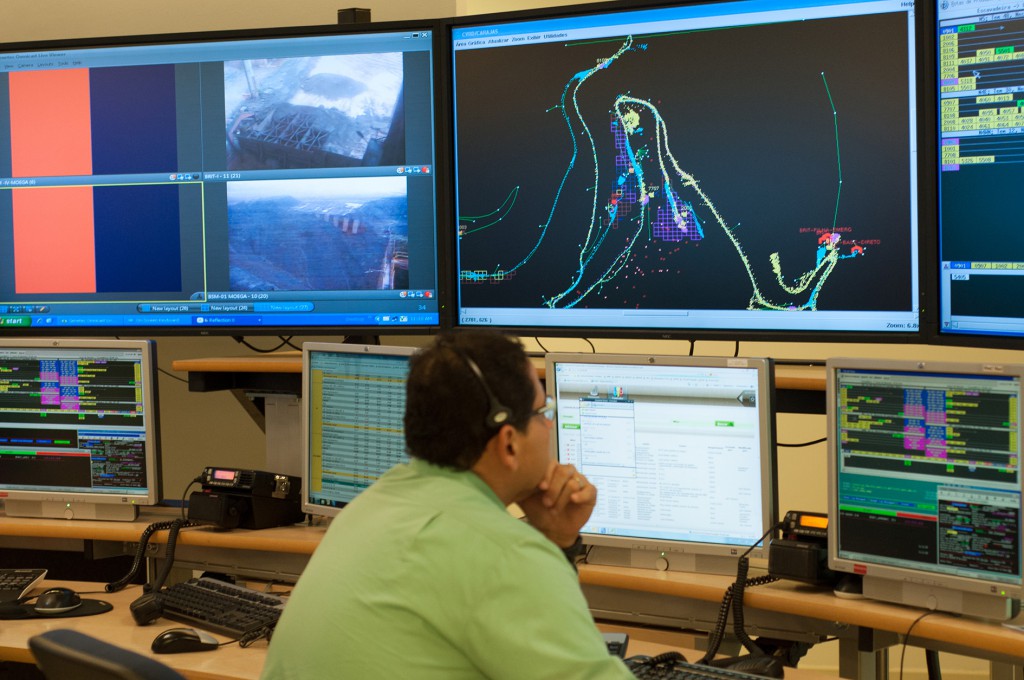

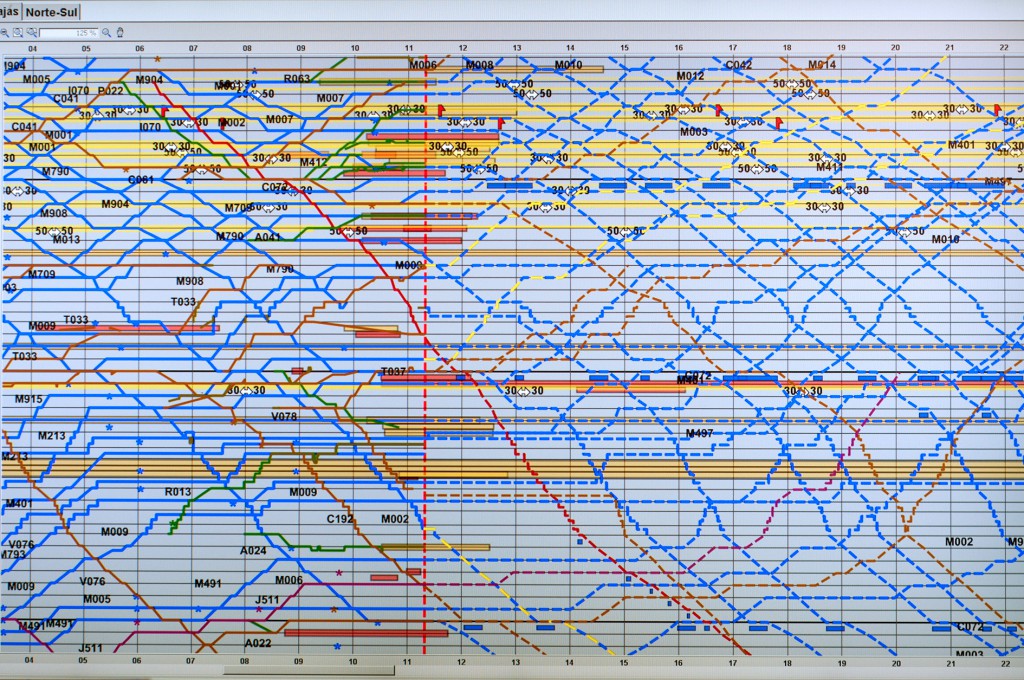

The performance of the frontier zone is defined by capacities. VALE Rio Doce, the world’s biggest iron-mining company and the operator of the Carajás mine, currently extracts an average of 110 million tons of high-quality iron ore per year, which accounts for around one-third of the company’s total production. In 2007, VALE approved an expansion project located 70 kilometers away from the existing one, close to the emerging urban center of Canãa do Carajás. The new mining complex, S11D, is scheduled to begin production in late 2016. At full capacity, Carajás and S11D will together produce a total of 230 million tons annually, whereas the total value of the investment will equate to $19.49 billion, out of which $11.45 billion will be logistics-related.

£The extraction and processing of the material goes on 24 hours a day, with overlapping work shifts. A company-owned, three-kilometer-long cargo train with 332 wagons runs three times a day in order to transport the iron ore to a deep-water port near the city of São Louis—and from there by ship to Asia and other global destinations. In view of the expansion of the complex, its logistical capacity will have to be drastically improved—VALE plans to add 600 kilometers of railroads, improve another 200 kilometers, build the Canãa dos Carajas Municipal Highway, and expand the Ponta de Madeira port terminal. The installment of the new mine, S11D, will create jobs for 30,000 people. However, due to revolutionary technological improvements—conveyer belts will replace most of the trucks iron mines have used in the past—the mine, once operational, will support only 2,300 long-term jobs.

What the staff overlooking VALE’s mining performance does not foresee are the impacts of mining on urbanization in the region. Beyond their technological achievements and the exorbitant numbers of their output, the sophistication of operations in the frontier zone has its limits. In view of the upcoming infrastructure projects, land-rights movements and local farmers have gone on alert. Are the economic interests for VALE and for the nation of Brazil so significant that the interests of sustainability and social justice have to be dismissed? What is more, how can the profits from mining be transferred to planning and producing better cities? Here and elsewhere, the frontier zone, while serving the interests of global capital, operates within other, local zones of arbitrariness, informality, and neglected landscapes.

2 Domestic Enclaves

Due to the remoteness of the location, life at the frontier is inevitably centered on domesticity. This becomes obvious in Núcleo Urbano de Carajás. The rainforest settlement was built in the 1980s for 6,000 employees at the mining complex. Its generous layout comprises one-story, single-family pavilions and practically all the services and public equipment needed to lead an upper-middle class lifestyle in the middle of the jungle. The community is surrounded by the Amazon forest; its gate stands at the entrance to the natural reserve, but additional fences protect the neighborhood from wild animals. There is even a zoo in the wilderness outside the fence for leisure activities and visiting guests—an enclave-inside-an-enclave where wildlife is preserved in cages. Núcleo Urbano de Carajás gives us the perfect illusion that nature and civilization can be conciliated, even at this very remote site. But the combination of domestic life and wildlife is highly orchestrated, and, after all, only viable through flight connections from the local airport to other urban centers. For the people who live in Núcleo, the tropical enclave is an exotic satellite, an extension into the Amazon that assures them that we do not really need cities there—just homes.

From the upper town of the Núcleo, a curvy road leads to the lower town, Parauapebas, which presents a completely different urban setup. Owing to about 300 meters of height difference, vegetation and even climatic conditions change between the upper and lower levels. Busy traffic on the only road that connects Parauapebas with the mine passes by another enclave—an aldeia, a traditional indigenous village that is organized around a circular square. Though the two enclaves are configured in completely different ways, they share the abundant flora of the tropical environment. But while in the Núcleo settlement the domestic regime is directly linked to mobility, logistics, and the economy of the middle class, the indigenous aldeia stands in close relation to the ecology of the forest. Can we consider nature as the liminal space that mediates between different economic and ecological regimes? In fact, for the people who live here, nature doesn’t play the role of bringing people together or representing the common ground that has to be preserved and respected. Rather the opposite is the case—the impenetrable vegetation of the Amazon offers many different natures, each of them dependent on how it is situated and how we make use of it. Like any other gated community, the tropical enclave is an anti-city where domesticity is encapsulated and isolated from the public domain.

3 Speculative Growth

It’s hard to say how many people live in Parauapebas; the numbers are constantly changing. With a growth rate higher than 12 percent per year and an estimated population of 250,000 inhabitants, the city can barely cope with the constant influx of migrants from all over the country. In view of the massive demand for housing, land prizes are skyrocketing, leading to aggressive real-estate speculation. As a result, the land value for formerly agricultural land transformed into lot divisions is often as high as in metropolitan areas such as Rio de Janeiro or São Paulo.

“In the speculator’s dream lay the urban promise—and the urban imperative—of frontier settlement and investment”: what William Cronon described as a theory of economic growth that dominated nineteen-century thinking about frontier developments turned, in the case of Parauapebas, into a handicap for any attempt to organize the city according to good urban governance.[2] Buildings here are built for the market; speculation not only prevents low-income renters from finding affordable housing in central areas, it also creates a fragmented and fractured city where the focus on profit keeps the city from growing in a coordinated and compact fashion.

In a place where as many as two homes are built each hour to meet surging demand for housing, grand intentions to seriously plan the city are constantly undermined. In view of the impossible task, the municipality chose to cope with the massive growth by privatizing infrastructure. Under this scheme, developers get concessions to divide land into lots and sell it if they guarantee the provision of basic infrastructure for water supply, sewage, and road access. But what the municipal government calls “assisted development” has turned out to be a burden on top of the original challenges and a serious obstacle to a comprehensive planning framework. As upgrading poorly built infrastructure shortly after its installation is more expensive than doing the job properly from the beginning, the municipality is slowly recognizing that keeping the control of infrastructural quality in public hands pays off in the long run.

For people who are unable to access the housing market, the lack of infrastructure becomes especially critical: the only alternative left to them is to build their homes illegally on squatted land. Living in precarious conditions, they suffer from inadequate water supply, insufficient sanitation, and the risks of flooding and landslides. In order to resolve the problem, the municipality has begun to prohibit wood construction, remove informal settlements, and relocate their residents to state-developed housing projects. With the ban on wooden houses, the local government hopes to formalize urban growth. As precarious as these structures might be, however,

While favelas in central areas are being removed, they continue to grow along the riverbeds and in proximity to newly built infrastructure. In light of the history of informal development, illegal building activity can be considered an integral component of speculative growth. The mechanisms of real-estate speculation and informality likewise pertain to the principles of privatization. If both informality and speculation are just different facets of urban production in place, the frontier town also teaches us how urbanization in the global hinterland can be seen as a byproduct of an economy that finds its interests somewhere else.

4 Tropical Wild West

The more people arrive, the more Parauapebas develops its own identity—the frontier town of the tropical Wild West gradually transforms into a city. Some of the busy streets, such as Rua do Comércio, are traffic-clogged thoroughfares reverberating with the buzzing of motorcycle taxis and car stereos blaring Tecnobrega, the thumping electronic music popular in this part of the Amazon. It’s hard to imagine that, until the early 1990s, Parauapebas was still composed of wooden houses, muddy roads, brothels, and no more than 25,000 inhabitants—a typical mining town at the margin of a barely urbanized region.

Back then, the population basically consisted of regional workers looking for jobs, prostitutes, bandits, and pioneers—people hoping for a prospering future in a place far from urban centers, out in the middle of the jungle. The promise of betterment, however, drags rural populations towards growing urban poles. Some researchers have argued that, in addition to allowing migrants to raise their living standards, migration to frontier cities might actually reduce forest loss by depopulating certain rural areas, allowing tropical forests to regrow. But others contend that migration may accelerate deforestation by permitting cattle ranchers, already responsible for razing vast portions of forest, to acquire and clear lands previously held by small cultivators.

Leaving the municipal boundaries, the whole dimension of deforestation committed by ranchers and owners of large estates becomes ever more graspable. But it’s not only ecological damage that makes the landscape of former tropical forest look so neglected and inefficiently used. Violations of landless farmers’ rights and even the use of slave workers are made evident by the signboards installed in front of the camps for the landless. They remind us that we are passing through a zone where civil rights have frequently been suspended in the course of the progressive exploitation of natural resources. In the middle of this wilderness, who can guarantee and control that the law is respected?

The most vivid illustration for the fact that the region has been controlled by outlaws and corrupt officials was the well-known massacre at Eldorado dos Carajás, where nineteen landless farmers, who were demonstrating for the expropriation of an unproductive ranch, were killed by the military police. The incident, which occurred in 1996, became a national scandal and revealed the extent to which the region’s development has relied on the abuse of power and the violation of law. Even today, the marginalized movements of landless farmers indicate that unjust land distribution and lack of agrarian reform are the major reasons for the devastating destruction of the Amazon forest.

5 Reshaped Land

Compared to the quantities of raw materials removed during mining operations, the flattening of hills throughout the city seems like a minor exercise. Even though the solid rocks, which are covered by a layer of red earth, contain up to 66 percent iron ore, the necessary machinery and technical skills are available for the reshaping of landscape. Streets are cut into the solid ground and building lots are laid out at a rapid pace. In order to simplify the process, in the preparation of the building lots existing vegetation is always completely removed.

Here, development is driven by feasibility—shaping nature is the precondition for the implementation of standardized construction. The main reason for the tabula rasa approach is that the real estate market prefers adapting the environment to suit proven, profitable building types over adapting the architecture to its context. What seems to be a wildly inefficient use of energy and materials simply follows the rational calculus of market-based development logic. Though the territory has already been modified through deforestation, the remodeling of the landscape adds another layer to the production of man-made natures.

6 Mass Housing

How many houses can be produced per day? For a municipality that receives roughly 25,000 migrants per year, time is a crucial factor. While construction companies are able to remove entire hills, building houses remains a challenge. Salim Rahal, associate of the construction firm JET CASA from Mato Grosso, proudly claims that their prefab system is able to produce up to nine houses each day if a local factory for the fabrication of the panels is installed. To date, there is no local company who would be able to compete with this output. It remains a difficult task for SEHAB, the Secretariat of Housing in Parauapebas, to attract contractors from elsewhere in Brazil to fill the gaps in an insufficient local building industry.

When quantity takes priority over quality, urban production proceeds via repetitive standardized models. The rapid pace of development also leads to absurd consequences; energy-intensive technologies are applied with no consideration of sustainability. Even so, the prescription of sustainable development is now written in bold on the municipal agenda in Parauapebas. Solar panels, for example, are commonly installed on the roofs of mass-produced houses. The sustainable technology is meant to reduce the energy bill for heating water—what hasn’t been taken into consideration is the fact that, in a tropical climate, alternative cooling systems would have a greater impact in reducing the overall energy bill. But never mind that—mass housing means generic production, and specific local conditions play a minor role.

The logic of generic housing production was introduced on a massive, national scale with the launch of the social housing program “Minha Casa, Minha Vida” (MCMV) in 2009. Tailored to boost the economy after the global financial crisis of 2008, the program’s declared mission was to tackle the housing deficit in the country—an estimated six million units. Within a four-year period, “Minha Casa, Minha Vida” aims to construct 3.4 million housing units; about half have been built so far. The largest social housing program in the world, it has been quite successful in giving low-income populations access to housing and, at the same time, attracting foreign investment for its implementation. Developed by construction companies in remote locations where land is cheap, however, MCMV developments stand for everything that goes against good urban planning. The mono-functional commuter settlements are poorly built; they lack public services, collective spaces, greenery, and even commercial units for local supply. As a consequence, the housing units are informally extended immediately after construction, turning into favelas or ghettos. Deficient infrastructure and unstable, bumpy roads have to be upgraded shortly after completion. What was meant to be a solution in many cases turns out to create even more problems. The program’s name—“My House, My Life”—represents the wish to create a new middle class of homeowner-consumers. But, although the dream of “your own house” has come true, access to the city is still missing. What could be an alternative development model for Parauapebas and other fast-growing Brazilian cities?

There isn’t much time for the municipal government of Parauapebas to answer such questions. If you want to catch up with demand, you have to act and get things done. In Nova Carajás, on formerly agricultural land at the periphery of Parauapebas, a new town for 25,000 inhabitants is on the way. The construction of MCMV houses is already contracted. Even here, in the middle of nowhere, land prices are high and, for the first time, the planning authorities are considering a denser neighborhood with four-story houses. Despite the fact that commuting to the mine on company-owned VALE buses will take up to three hours per day, the rush for the new housing units has already started.

Nova Carajás is just one extension zone in a city where urbanization follows a fragmented, piecemeal logic. Still more problematic than MCMV developments are the gated middle-class communities and closed condominiums dispersed through the urban fabric. Attended by large shopping malls and privatized leisure spaces, the city is now entering a new phase in which the whole range of generic models is arriving in the middle of entropic urban growth. “The Zone” as a model that guarantees the continuous flow of goods and capital is also affecting the margins of a frontier that no longer serves as a backwater, but rather as a new urban centrality amidst the abundance of a remodeled nature.

7 The Natural City

Does Parauapebas have a future beyond and independent from mining? The municipal planners still have a long way to go to realize this vision. The extraction of natural resources has been a blessing and, at the same time, a disaster for the urbanization of the region. The city’s love-hate relationship with the mine also expresses the dilemma of uneven distribution of natural resources and its consequences for the local population. What if there were an alternative way to link urban development with nature? The task of making a home in nature obviously has to be addressed at both ends. The preservation of the natural environment alone will not sustain future livelihoods. So how can we make use of nature in a more productive sense? Here in the middle of a natural and urban wilderness, the answer might be found in a natural-urban culture. “The only thing we have to preserve nature with is culture; the only thing we have to preserve wildness with is domesticity.”[3] As preservation has to deal with a new culture of development, the frontier zone marks, at the beginning of the Anthropocene, the tipping point where nature and city intensively meet. What the Natural City Parauapebas ultimately shows us is that there is no city without nature—and, in turn, there is no nature without culture.

Text by Rainer Hehl

¹ The term refers here to Keller Easterling’s definition of the “Zone.” Keller Easterling, “Zone,” in Urban Transformation, eds. Ilka & Andreas Ruby (Berlin: Ruby Press, 2008).

2 William Cronon refers here to the Booster’s economy of Chicago’s mid-west, who saw the engine of western development in the symbiotic relationship between cities and their surrounding country sides. William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis, (Norten & Co, 1992), p.34.

[3] Wendell Berry, Home Economics (San Francisco: North Point, 1987), 138.