EMPOWER

On the Political Economy of Urban Form. Empower!

Ruby Press, Berlin 2014

Urbanization in the Age of the Anthropocene

“If there is material, technological, and industrial pollution that exposes the climate to conceivable risks, there is a second, invisible pollution that endangers time: cultural pollution to which we have subjected the thoughts of the long term that are the Guardians of the Earth, of men, and of things themselves. Without fighting this second pollution, we will lose the battle against the first. Who can doubt, today, the cultural nature of what we call infrastructure?”1

Michel Serres, The Natural Contract

At a time when repressive authoritarian regimes frequently undermine major struggles for political democratization, we must ask ourselves whether the prerequisites for empowerment have to be reframed. What the current protests and revolutions for democracy tell us is that large segments of the world’s population are excluded from decision-making. In view of the dominance of market interests and the paradigm of ongoing economic growth, nothing seems more obvious than to empower “the other 99 percent” in order to restore the delicate and conflict-prone balance between the many and the few. Redistribution of power represents the only viable way to overcome the crises we face, whether economic, social, or ecological. However, in a world where capital interests drive the management of the globe, political empowerment doesn’t necessarily ensure socially inclusive or ecologically sustainable development. And considering the ongoing struggles, does empowerment really provoke systemic change? Who, in the end, benefits from empowerment? Or, in the words of Ananya Roy “If the democratization of capital and the democratization of development are key themes of the new millennium, then it is worth asking: Who are the users of this new global democracy? Who is thus empowered?”2

While the recent push for political democratization has become central to the process of redistributing power, it remains, in many cases, an unredeemed promise. The difficulties encountered by pro-democracy groups, as in the Arab revolutions, as well as by those agitating against the dominance of market interests—such as the American Occupy movement, the Spanish Indignados, and like-minded protestors in Turkey and Brazil—illustrate how resilient existing structures can be. But they also show that governing regimes persevere because their power is rooted in economic and financial operations that are essential to our entire operating system. How can we empower the people if the institutions with a monopoly on power are just too big to fail?

Instead of just looking at political struggles, we have to open the black box of “developmentalism,” the various procedures and transactions that make the natural environment inhabitable in the long term. As a matter of fact, if we focus on the current mode of urban production—in which capital and resources are becoming scarce—empowerment can be understood via a wider perspective. By reframing the relationship between manmade and natural environments, we shed new light on the question of what kind of empowerment truly is needed on the way to a more sustainable world order.

Proclaimed by the climate scientist Paul Crutzen in the early 2000s, a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene, marks the point at which humans have altered the environment so extensively as to blur the distinction between culture and nature, inscribing ourselves into geological time.3 What is so striking about the declaration of this new, manmade epoch is the fact that human culture is now so powerful that the future of the planet pretty much depends on the way we operate “spaceship earth”—empowerment has actually become the driver for the construction of the world. If we take the task of shaping and managing the planet seriously and proactively, the role of the architect and planner will become ever more crucial. They will be “comprehensive designers,” assembling the knowledge and the forces necessary to produce the habitats of tomorrow.4

Although the message of a new planetary epoch is not new, the proclamation of the Anthropocene indicates a new dimension of human influence on natural history. Rather than just dissolving the borders between “nature” and “culture,” the impact of human interventions into the planet has reached geological proportions. In the context of an ecological paradigm, human responsibility is no longer just related to the preservation of unspoiled areas and the idea of a future civilization that has made its peace with nature. Instead, we desperately need socio-technological skills to meet the massive demand for resources and labor required by the rapidly ongoing processes of urbanization.

In the Anthropocene, the reach of political struggles claiming more power for the people has to be revised. If the introduction of “political economy” in the eighteenth century was aimed at the organization of populations, territories, and wealth, governmental practices today are designed to sustainably manage our massive demand for natural resources. The shift from the science of “political economy” to the new discipline of “political ecology” foregrounds negotiation processes between manmade and natural environments. More than ever before, architecture and urban planning are playing a major role in shaping the physical environment. The promotion of a “political ecology of urban form” not only brings ecological concerns into the equation, it also indicates that the Anthropocene epoch demands a new culture of urban development.

While the consequences of our transition into the Anthropocene have been widely discussed within and across various disciplines, its impact on the production of urban form remains underexposed. The present collection of essays extends the discussion around the Anthropocene to its effects on urban production and planning practice.

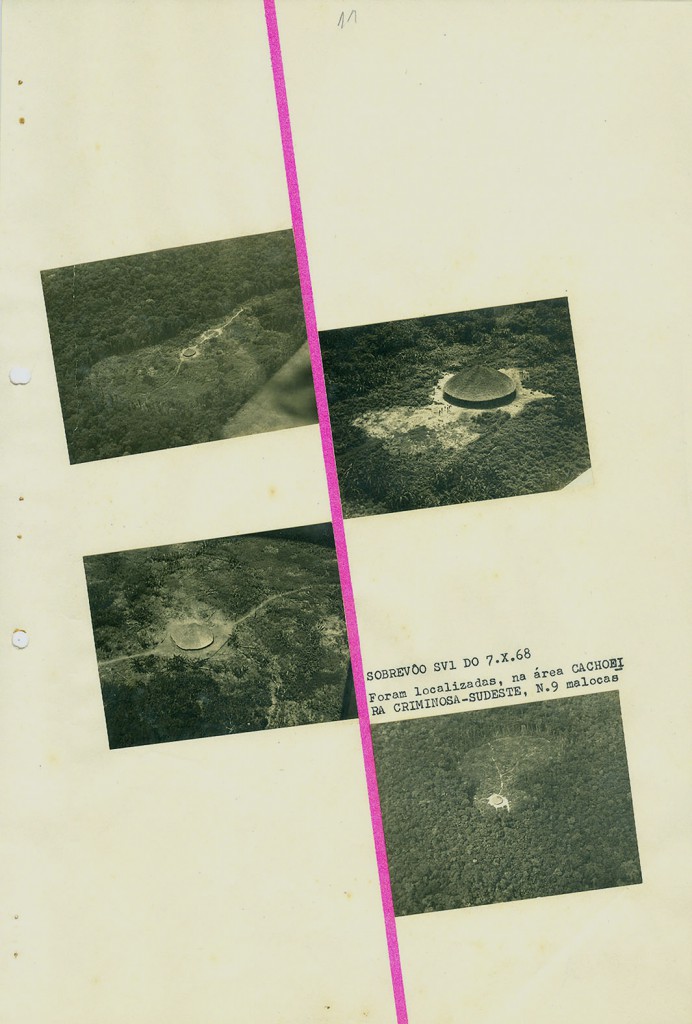

Paulo Tavares, in his essay “The Geological Imperative: On the Political Ecology of Amazonia’s Deep History,” reveals how the lack of a sustainable development culture has affected territorial planning in the Amazon basin, which contains half of the planet’s remaining rainforests. Under the paradigm of economic growth, developers have sought to convert the entire basin into a “massive frontier of resource extraction and agricultural production.” “The Geological Imperative”—the title refers to a report by the same name published in 1976—makes a case for political engagement through anthropological practice; it also demonstrates that ethnocide and ecocide are both manifestations of this culture of exploitation.

In her essay on “The Geopolitics of Subtraction,” Keller Easterling counters the prevalent development paradigm, proposing the removal, or subtraction, of existing infrastructure. While looking at the case of Ecuador’s Yasuní-ITT initiative, which sought to protect a natural reserve by soliciting international funding to not extract the vast amounts of oil that lie beneath it, Easterling argues for subtraction as a way to preserve the natural environment—and even as an economic growth model. The removal of infrastructure follows the agenda of a new development culture in which “unbuilding” is a major component in the renegotiation of the prevalent matrix of spatial protocols.

Rahul Srivastava and Matias Echanove, in their essay “Circulatory Urbanism,” explain how cheap, accessible public transportation can empower low-income workers. Studying the railway networks on the Konkan Coast around Mumbai, they conclude that enhanced mobility makes categorizations like the “megacity” or “large urban agglomeration” obsolete. Navigating between rural and urban environments, many migrants to Mumbai ”belong” to multiple places—their native villages as well as the cities where they live and work. Their commuter patterns lead to circulatory urban systems—a new type of low-density urbanism that challenges previous notions of the periphery and urban sprawl.

The last contribution to this publication, “Natural City Parauapebas—Notes on Development Culture in the Global Hinterland,” takes the Brazilian mining town Parauapebas, located on the edge of the Amazon forest, as an allegory of and model for urban development in the Anthropocene. The case of Parauapebas is of particular interest because it reveals urbanization patterns on one of the world’s last frontiers; driven by massive global demand for natural resources, population growth in Parauapebas is among the fastest in the country. While urbanization is usually problematized on the basis of urban centers or agglomerations, this journey to the global hinterland reveals how far large-scale, market-dominated urbanization operates through generic patterns. This report from Brazil’s Wild West also raises the question of whether the development of new towns in close relationship to the natural environment can lead to a new urbanization paradigm. Parauapebas, in this sense, represents not a remote, subsidiary location, but rather a test case for emerging urban spaces situated amidst still unexplored natural resources, squarely within the conflict zone between global and local demands.

At the beginning of our new, manmade epoch, did we lose the sense for building good cities? As early as 1994, in his essay “What Ever Happened to Urbanism?” Rem Koolhaas argued that, right at the moment when urbanism is most desperately needed, the notion of the city is vanishing. Paraphrasing his statement, we can proclaim now that “more than ever, the city and nature are all we have.”5

Inroductory text by Rainer Hehl

1 Michel Serres, “The Natural Contract,” Critical Inquiry 19 (1992): 5.

2 Ananya Roy, Poverty Capital: Microfinance and the Making of Development (London: Routledge, 2010).

3 According to climate scientist Paul Crutzen the Anthropocene could be said to have started in the late eighteenth century; analyses of air trapped in polar ice pinpoint this time as the beginning of the ongoing concentration of carbon dioxide and methane in our atmosphere. See Paul Crutzen, “The Geology of Mankind,” Nature 415 (2002): 23.

4 The term “comprehensive designer” was used by Buckminster Fuller to suggest the architect’s new role as a combination of inventor, artist, engineer, economist, and “evolutionary strategist.” See Buckminster Fuller, Ideas and Integrities: A Spontaneous Autobiographical Disclosure (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1963).

5 See Rem Koolhaas, “What Ever Happened to Urbanism?” in S,M,L,XL, Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, eds. (New York: Monacelli Press, 1995), 971.