APB in the making

“The ‘making’ in question is a production, a poiesis—but a hidden one because it is scattered over areas defined and occupied by systems of ‘production’ (television, urban development, commerce, etc.), and because the steadily increasing expansion of these systems no longer leaves ‘consumers’ any place in which they can indicate what they make or do with the products of these systems. To a rationalized, expansionist and at the same time centralized and clamorous, spectacular production corresponds another production, called ‘consumption.’

The latter is devious, it is dispersed, but insinuates itself everywhere, silently and almost invisibly, because it doesn’t manifest itself through its own products, but rather through its ways of using the products imposed by a dominant economic order.”

Michel de Certeau, The Art of Making¹

The Power of Productive Consumption

Against the belief that globalization would render the world as a homogenous and generic field controlled by market interests urban realities on the globe are becoming more and more diversified and locally specific. Under the reign of globalized economic order urban production is increasingly generated by popular masses and processes beyond control—it is projected that in about 20 years more than half of the urban population will live in ‘informal cities’.

If city growth in the future will be predominantly driven by urban informality, parallel governance and self-organization, then the question is whether these sub-systems represent alternative models for urban production or if they are rather integral components of the prevalent economic order. What is more, in view of the advance of informal urbanization can we consider the production by the people as localized, countercultural projects against the dominance of the globalized market system?

The case of the tropical metropolis in Brazil gives us an insight on how popular culture is affecting the market economy and vice versa. While urban production in Brazil is on one hand determined by generic standardized models and uncontrolled informal growth on the other, the notion of popular production represents another category forming the middle-ground where generic and specific meet. But who exactly are these popular producer-consumers? Which are the population groups that are sustaining the popular economy? In Brazil the composition of what can be understood as popular masses has drastically changed during the last 10 years, which is mainly due to transformations of income distribution. With the emergence of the lower middle-class, which represents nowadays the biggest segment of the Brazilian society, low-income populations have now increasingly access to consumer goods—today these new consumers are actually considered the main target for future market expansion and the driver for economic growth.

Collective Mobilization

Nobody expected anything as radical would happen on that day. According to official media on June 20th 2013 1.2 million people were filling the Rio de Janeiro’s streets raising their voices for more democracy and participation. A wide range of the Brazilian society, young people, popular movements and enraged citizens were demonstrating against the operating mode of an established system that doesn’t take enough care of the people’s needs. Brazil has never seen a similar mobilization of protestors claiming for public interests in its whole history. What was the motivation for the upraising of the masses and the sudden explosion of a huge amount of collective energy? Whether the protesters claimed for thorough action against state corruption or for more investment in education, social security and public transportation, one message was clear: from now on things have to change.

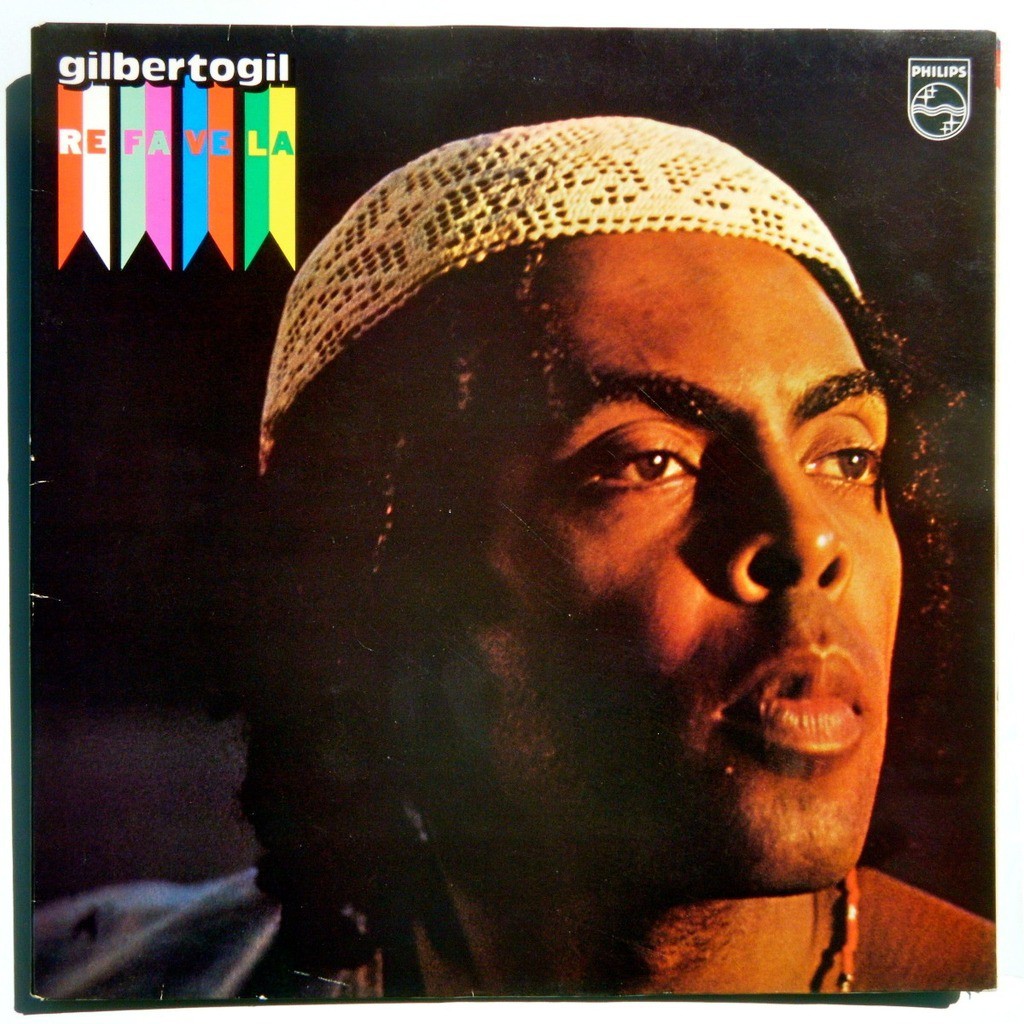

When the Brazilians were living a similar moment 45 years ago 100.000 people were occupying public spaces, fighting against state oppression during the military dictatorship, and singing in the streets that “tomorrow has to be another day” (amanhã há de ser outro dia), a song-line, which was written by the Brazilian singer-songwriter Chico Buarque, who can be associated with the music genre MPB—Música Popular Brasileira. The street protest gave rise to the formation Tropicália, which soon became known as an ephemeral, but high impact movement. Led by MPB artists including Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso and others Tropicália was about the appropriation of local and foreign music styles in order to relativize prevailing notions of authenticity in Brazilian music. The movement radically altered the field of popular music, creating new conditions for the emergence of eclectic and hybridized experiments, but it also defined an inaugural moment for a broad range of artistic practices and behavioral styles identified as “countercultural” during the period of military rule. Up to these days Tropicália is considered as an artistic movement addressing the creation of a cultural identity across the whole spectrum of the Brazilian society in the moment when the country was increasingly experiencing political repression and social segregation.

What do the recent uprisings in Brazil have in common with the protests against the oppressive regime? For what kind of change is it standing for? The moment when the recent protests occurred Gilberto Gil, the former minister of culture and one of the most prominent figures of the tropicalist movement was drawing parallels between what happened back then and now, asking if the uprisings that are occupying the streets today are strong enough to change the reality. Concerned about the monstrous dimension of the riots, but at the same time relieved to see this popular insurgency happening again, he saw a common denominator between the countercultural movement of the past and the kind of mix between rave and raid (rave-arrastão) that we experience today. What is more, according to his interpretation the protests are revealing a phenomenon that applies to the recent global condition dominated by a neoliberal economic system: the ongoing reproduction of asymmetries between the ruling classes and the popular masses – the increasing gap between rich and poor, high and low culture, between top-down governance and bottom-up mobilization.

Counter Culture

The tropicalist movement was rooted in local and at the same time in transnational identity by adhering consistently to international pop-culture and hybridizing Brazilian music styles with foreign influences. Tropicalism was understood by its followers as “superantropofagia”, as re-edition of cannibalistic rituals aiming at the incorporation of the enemy’s forces. But unlike the early modernist attempts to appropriate the cultural avant-garde of the former colonizers, the tropicalists were more interested in the making of popular culture rather than introducing the notion of the popular in the artistic language of the cultural elite. Within the wide range of MPB (Música Popular Brasileira) the tropicalist sound was invented for the avant-garde as well as for the consuming masses. As a matter of fact, the popularity of its proponents is still transgressing today the boundaries between classes and nationalities. When Gilberto Gil released his album entitled “Refavela” in 1977 with the song-lines “The refavela reveals the paradoxical Samba school, quite Brazilian in its accent—but international in its language”2 the claim for cross-cultural exchange is expressed in the paradox of being rooted in different value systems at the same time. Similarly Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica reclaimed Anthropophagy with a show that he organized in 1967 featuring several pieces of young Brazilian artists including his own work entitled “Tropicália”, which further on turned out to be used as the name of a whole movement. With his inaugurational presentation Oiticica intended to extract ‘from individual creative efforts the principal items of these same efforts, in an attempt to group them culturally’3.The message of the operation was clear—the gathering of collective forces was meant to designate the creative will of a culture in the making. With a spatial arrangement of the specific milieu that he experienced in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro Oiticica imagined in his installation a re-founding of Brazilian culture by drawing from a peripheral position. Rather than just decontextualizing the favela experience within the museum space his installation Tropicália was about translating images of “Brazilianness” in order to be internalized and redeployed by cultural producers. In line with Andrade’s slogan “Only Anthropophagy unites us.”4 the tropicalist mind-set wasn’t only open for devouring adversaries but it also practiced the reverse process engaging in the “powerful sense of being devoured.“5 It was by embracing the differences of the other that the tropicalist movement opened the path for a dialogue between high- and low culture—between the aspiration for the avant-garde by the cultural elite and the fragmented and heterogeneous body of the popular masses.

Consumer-Producers

Back then it was rather clear against whom or what to resist. In the face of governmental repression, whether this applies to the military regime or to the dominating order of the police state, it was easy to identify the enemy.

If we look at the current situation things turn blurry while searching for responsible parties for today’s deplorable state of affairs. While power is exercised and operated by an economy that ensnares us in a fine weave of dependencies it is actually quite hard to find an oppositional position. Can we truly fight against dominating corporate interests while being consumers that guarantee at the same time the operational mode of the current economic system? Are there still alternatives that can be developed within or against the operating system of market-driven interests? What is more, are the popular masses just subject of a consumer culture that is following the preconditioned behavioral patterns of the globalized market economy?

Michel DeCerteau states in his book on The Art of the Everyday that the operational models of popular cultures cannot be confined to the past, the countryside, or primitive peoples. They exist in the heart of the strongholds of the contemporary economy. By defining the main field of popular action within the framework of the prevalent economic system and related modes of production DeCerteau positions the consumer as a crucial actor in the process of the formation of cultural identity. With an emphasis on the various “ways of using the products imposed by a dominant order”6 the rituals of everyday practice are considered as the main driver for the resistance to an imposed order. Rather than questioning the constitution of established power constellations, DeCerteau is interested in the question what the consumer finally does with consumer products and whether consumerism can create its own local identity by emphasizing the fact that acculturation is mainly determined by individual and collective appropriation.

Popularization

“In reality, a rationalized, expansionist, centralized, spectacular and clamorous production is confronted by an entirely different kind of production called “consumption” and characterized by its ruses, its fragmentation (the result of the circumstances), its poaching its clandestine nature, its tireless but quite activity, in short by its quasi-invisibility, since it shows itself not in its own products (where would it place them?) but in an art of using those imposed on it.”7 In order to illustrate his claims DeCerteau refers to the practices of certain indigenous Indian cultures in face of the dominating order of Spanish colonization. What turned the suppressed people into creative consumer-producers was namely the fact that the “Indians often used the laws, practices, and representations that were imposed on them by force or by fascination to ends other than those of the conquerors.”8 The subversion of the ruling power was exercised without leaving the system—the procedures of consumption allowed to “remain other” by making the prevailing order functioning in another register. Against the generic logic of market-driven consumerism DeCerteau opposes a process of “popularization” while addressing the question what the end-users finally make out of the commodities that are offered to them.

The act of creative appropriation becomes most obvious in the contemporary context when we look at the parallel modes and tactics as deployed within the conditions of urban informality. In line with DeCerteau’s argumentation the lessons from the favelas can be found in the various ways the formal system is diverted in order to adapt to the conditions of local characteristics and the necessities of everyday life. Instead of just being a subversive regime that creates an alternative reality according to its own rules, informality is complementing the formal system by introducing new value chains that are adapted to the specificity of the local milieu. However, while urban informality can also be seen as just another kind of manifestation of the neo-liberal market logic, the reinvention of the everyday will only be achieved through the ruses and tactics of popular appropriation.

Everyday Tactics

If strategic maneuvers can be described as calculations of power relationships deployed by subjects with will and authority (a business, an army, a city, a scientific institution), a tactic refers rather to “the art of the weak”—or in the words of DeCerteau “Lacking its own place, lacking a view of the whole, limited by the blindness (which may lead to perspicacity), resulting from combat at close quarters, limited by the possibilities of the moment, a tactic is determined by the absence of power just as a strategy is organized by the postulation power”. Accordingly the ways in which tactics are exercised are intrinsically related to the notion of time. Inscribed in specific timeframes tactics are therefore always operating “within the enemy’s field of vision”, whereas strategies depend on spatial logics and territorial claims in order to be effective. The absence of a proper locus is what makes a tactic weak and vulnerable but also flexible and adaptable to the dynamics of a constantly changing reality.

Popular tactics are still quite present within the public realm of the Brazilian streetscape and most efficient if it comes to finding a way out of regulations imposed by public authorities. Invented by popular ingenuity the cavalete, a device that serves for a mobile market stand, embodies all of the virtues of popular Brazilian street culture. The components of the foldable system—sticks from scrap wood, aluminum hangers and bunch of screws— are assembled by local manufacturers and only distributed in specific selling points in the streets. The elegance of the construction is resulting from the most important functionality of the system. Once control by public authorities is in sight, the cavalete construction can be dismantled in seconds in order to eliminate rapidly the proof for illegal activity. Or think of the camelôs (street-vendors) who appropriate the space of public transportation—those who sell candies wrapped in bundles hanging from a hook, which eventually hangs from the handles inside public busses. The ingenuity of the attachment system seems just stunning. It’s not only the practicality and simplicity of the hanging version of a candy stand that makes the solution so convincing—it is also accompanied by a certain elegance in the unconventional use of the laws of gravity, constantly poised for flight should the vendor need to flee from the police.

Shock of Order

As the tactics of the popular economy are considered subversive to the established formal order and corporate interests, the popular culture of street vending in Brazil is nowadays getting more and more restricted by new laws and regulations concerning their use in public spaces. In fact, the policies recently introduced in Rio de Janeiro on the pretext of sanitation and security, are actually banning a great deal of the popular street culture for the sake of public order. The operation Choque de Ordem (shock of order), set in motion in 2009 by the City of Rio de Janeiro in collaboration with the Special Secretary of Public Order (SEOP) and the municipal cleaning company (Comlurb), is based on the conviction that the streets of Rio have to be cleaned up in various ways: by increasing trash collection, shutting down illegal commercial activities, such as unlicensed vans and street vendors, and enforcing laws relating to public decency. With the enforcement of order, informal street activities and spontaneous pop-up selling points are prohibited in favor of a more formalized corporate economy. In its most pervasive logic the control of public space for corporate interests has been exercised during the World Soccer Championship in 2014. As a consequence of contractual agreements between the FIFA and the municipal governments a special commercial zone was installed around the soccer stadiums. The proposed legislation prohibited the sale or display of any merchandise at the “Official Competition Venues, in their immediate vicinities or in their main points of entry”, without FIFA’s express permission.

The contracts illustrate very clearly the spatial strategy behind dominant market forces. While popular products are increasingly subject of corporate protection the appropriation of urban spaces through everyday practices is suppressed in favor of very specific process of social engineering—as a result public space ceases to be a place for popular economies and local production.

If the everyday still aims to enter the public realm new tactics have to be invented that are able to cope with the perfidious strategies of the corporate system.

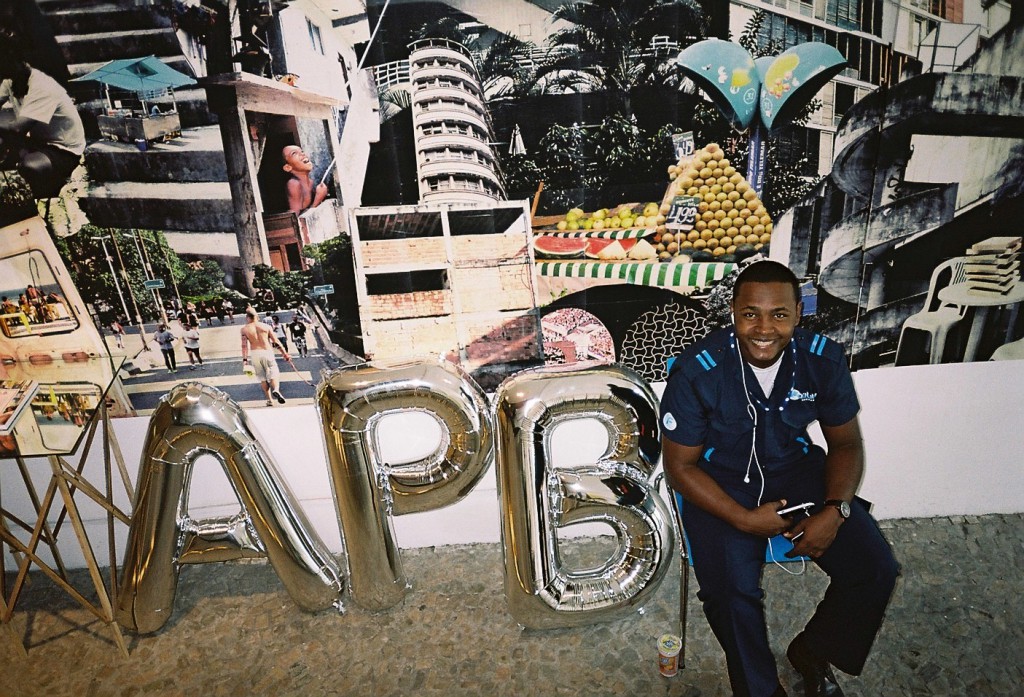

Popular Brazilian Architecture

It might be a pure coincidence that another event happened on June 20th 2013 in Rio de Janeiro at Praça Tiradentes in immediate proximity to the revolting masses. In the middle of a sudden outburst of collective discomfort APB, research on “Popular Brazilian Architecture”, was presented to a local crowd. The specific culture of Brazilian spaces was held against the generic model of Brazilian mass housing, “Minha Casa Minha Vida”. On the backdrop of the upcoming turmoil in the surrounding even government officials realized the urge for change. What would be the contribution of an identification of popular Brazilian culture to the current conflicts?

The documentation on popular culture is shedding a positive light on the everyday of lower- and middle-class residents rather than revealing the harsh reality of daily struggle. With the eye of an outsider to the investigated culture, building elements, street activities, construction methods, floor plans, public furniture and other components were collected that seemed to make a fundamental contribution to the richness, vitality and creativity of Brazilian spaces. The APB collection was elaborated as „generative grammar”, which opposes abstract formal design methods, favoring empirically acquired knowledge upon observation and experimentation, promoting a radical belief to a timeless way of urban production, grounded on centuries of trials. With a deep interest in the modalities of everyday practice APB is collecting tools that provide all qualities needed to enable Brazilian popular cultures and to reinvent them in the same time.

If half a century ago the Tropicalist movement transformed the traditional notion of popular production in Brazil into an open process of cultural creation, an investigation on popular architecture could have a similar impact in the context of the social transformations that are happening today. Whether we look at the experimentation of collective action in the streets of Rio or at the emerging interests in APB – Arquitetura Popular Brasileira, June 20th 2013 marked the beginning of a new era of popular movements in Brazil, but it also offered the opportunity to rethink design practice as a powerful tool for the reproduction and reinvention of popular culture beyond class segregation, and, eventually for the realization of a truly popular Brazilian architecture.

1 DeCerteau, Michel 1984, The Practice of Everyday Life, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, p.xxi

2 Original song-line “A refavela / Revala a escolar / De samba paradoxal / Brasileirinho / Pelo Sotaque / Mas de língua internacional.”

3 Original source: Oiticica, Hélio 1967, ‘Esquema geral da Nova Objetividade Brasileira’, exhibition catalogue, Museo de Arte Moderno, Rio de Janeiro. First translated into English in Oiticica Hélio 1992, ‘General Scheme for New Objectivity, in: Hélio Oiticica, exhibition catalogue, Witte de With and Walker Art Center, Rotterdam and Minneapolis

4 Oswald de Andrade’s manifesto, which starts with the lines “Only anthropophagy unites us. Socially. Economically. Philosophically.” was first published in: Revista de Antropofagia, No.1, São Paulo, May 1928. English translation by Maria do Carmo Zanini in 2006

5 Oiticica Hélio 1992, ‘Tropicália’, in: Hélio Oiticica, exhibition Catalogue, Centro de Arte Hélio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro, p.124

6 DeCerteau, Michel 1984, Ibid., p.xxi

7 DeCerteau, Michel 1984, Ibid., p.31

8 DeCerteau, Michel 1984, Ibid., p.31